A robot for unloading containers is being developed in Bremen

Maritime economy and logisticsThe IRiS robot is set to handle up to 800 packages an hour by 2020

Unloading 40 foot long shipping containers involves heavy manual labour. It can be difficult to find people willing to do this kind of work, so the Bremen Institute for Production and Logistics (BIBA) is developing a robot to take it on. BIBA’s partners on the IRiS federal research project, which is set to cost €3.16 million, are BLG LOGISTICS, Munich-based image processing specialist FRAMOS and Bremen-based SCHULZ Systemtechnik.

Britta Philipsen, site manager at BLG’s Neustädter Hafen logistics centre, invited all parties to the centre shortly after the IRiS project was launched in September 2017. Her reason for inviting the partners to Europe’s largest high-bay storage facility was to ensure that they are aware of the size of the task. “You have to get an idea of the dimensions we are dealing with here,” says Philipsen, a logistics expert whose degree dissertation at Bremen University explored innovation management at logistics service providers. The site near Bremen’s Cargo Distribution Center (GVZ) houses 200,000 pallets and turns over up to 8,500 of them every day. “Doing this manually is no longer an option,” says Philipsen.

Innovation in port technology

Traditionally, the logistics service sector is very labour intensive, but like any other industry it is affected by technological change, according to Philipsen. The unloading of shipping containers is one of the few non-automated processes left in the logistics chain. And this is where the IRiS robot can help. The Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure made €3.3 million available from the IHATEC programme, which specifically supports innovative port technology, to fund the project.

Philipsen names three reasons why BLG opted to take a 50 per cent stake in the research project: “I really struggle to hire people to do this job. These days, very few people are willing to unload containers.” She hopes that IRiS, the interactive robotic system for unloading shipping containers, will remove the burden from her employees in the long term: “It’s also a question of health and safety. Providing technological support for such heavy manual labour makes sense.” She is also looking to retrain her existing workforce and turn them into machine operators, for example. And an additional benefit of acquiring new skills is better pay.

Her employees are working with Philipsen on the project: “Technological change needs to be communicated properly to ensure that employees accept it. Including our foremen and coordinators in the initial workshops has been an important part of this. My colleagues provided their input and are now set to introduce the new technology in two years’ time.”

There are charts showing the KPIs from recent weeks on the noticeboard. This is a sign of a modern organisation – plant management does not keep this type of information to itself. Alongside this are some initial diagrams that explain the IRiS project to the employees. The current project’s predecessor is also mentioned, although that particular robot was not well received. “It was just too massive. Whenever there was a problem, the robot had to be removed from the container by hand before work could continue, and that wasted too much time,” says Philipsen. Technical issues were not supposed to cause downtime for motivated staff.

Dr Hendrik Thamer, who works at BIBA, the lead partner on this project, believes the experiences gained on previous projects have positively influenced IRiS: “We have learned a lot, and are now developing a highly mobile solution – that is to say drivable and lightweight. It will no longer require an expert to operate it. Everything will work using control units of a type that will be familiar from games consoles.” But most importantly, as mentioned above, the employees have been fully involved in the development process. This is a significant change to the previous project, according to Philipsen.

IRiS has to get it right

The specifications list all the things that the robot should be able to do. And one thing is certain: IRiS will be stronger than a person and look quite different to its human colleagues. The robot will be able to extract several boxes from a container in one go, turn them and distribute them on the conveyor belt. Each box can weigh up to 35 kilos. “The robot must be able to recognise things such as the markings on the top of a box. After all, you only need to place a box full of porcelain upside down once to ruin the contents.”

The dimensions of the boxes will also vary, and the robot will need to be able to handle this. The minimum turnover is currently set at 800 boxes an hour. As Philipsen explains, there is a specific reason for this figure: “We looked at how much we are turning over now. IRiS will need to achieve at least the same performance as we do on our top 10 per cent of days, otherwise its deployment won’t be viable.”

Dr Thamer at BIBA hopes to achieve an 80/20 split for IRiS: “The machine will do 80 per cent of the work, and humans the other 20 per cent. The machine doesn’t need to do everything. Humans are able to use their superior cognitive abilities far quicker in the event of a problem than a robot can.” FRAMOS, based in Taufkirchen near Munich, is providing the sensor systems and the artificial intelligence. These systems allow IRiS to recognise the type of box it is dealing with. Laser scanners on the sides of the robot create a safety area. If a person enters this area, the robot performs an emergency stop.

The design of the gripper is taking shape

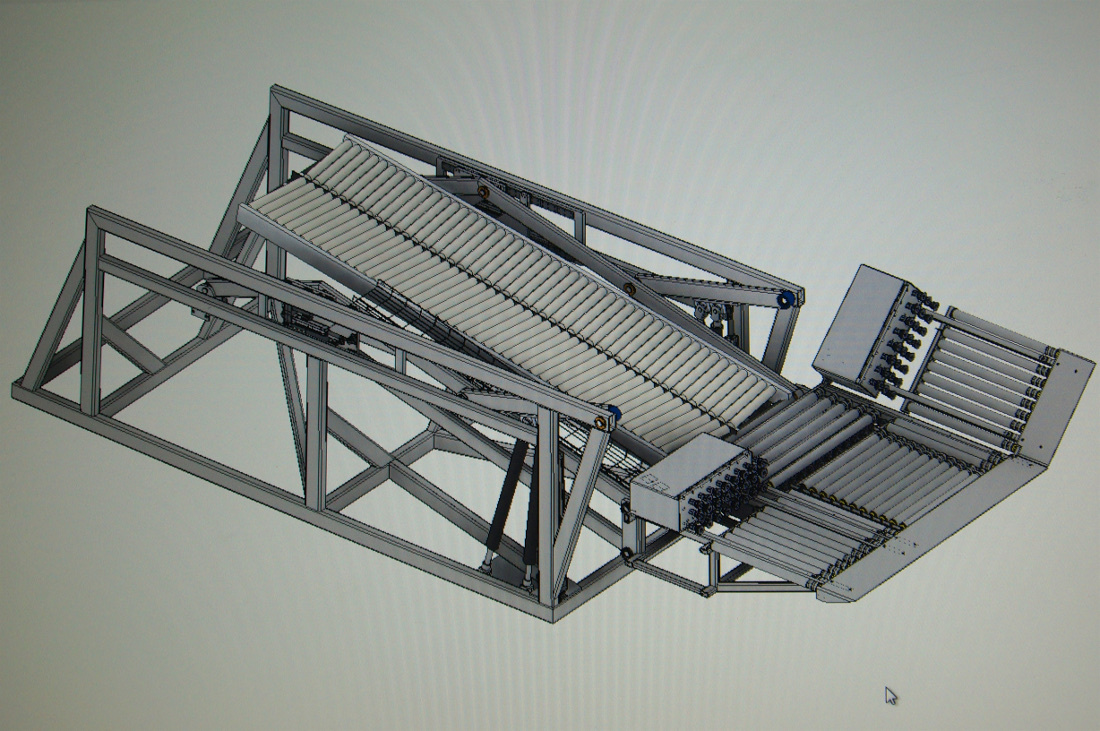

In order to get an idea of the progress on the project, we visit the BIBA institute in the technology park near Bremen University, where 150 employees are developing bespoke solutions for regional businesses. Dr Thamer’s robotics department itself has ten employees. Although only a few months have passed since the initial meetings with the partners, mechanical engineer Nils Hoppe’s screen already reveals an advanced basic frame, even if little of the internal workings of IRiS are visible yet. The running gear is also missing, but Hoppe has made good progress with the gripper: “These plates with suction pads are extended forwards. When they come into contact with a box, the pads are activated and the box can be pulled out.”

It takes a lot of power to get several boxes moving in one go, so he intends to add counterweights to the other end of the extended gripper, similar to the ones found on a crane. These should reduce the amount of power required and keep the system’s bulk to a minimum. The IRiS robot’s dimensions are around five metres by two – plus the wheels and the running gear, which is yet to be created. Regular meetings and fortnightly phone conferences keep everyone up to date. “So far, everything is proceeding as planned,” Dr Thamer says of the project, which is set to run until 31 August 2020.

The robot is tested using simulation programmes developed by SCHULZ

To ensure that the development runs smoothly, and to provide digital support, experts from SCHULZ Systemtechnik’s Bremen site are involved in the project. With the help of their simulations, it is possible to identify all imaginable problems in advance and run through them virtually. The developers at BIBA do not regard this as unnecessary interference in their work. As Hoppe explains: “SCHULZ have created a digital twin based on our design that we can use to simulate entire movement processes and identify any unforeseen problems. We can put the entire system into operation virtually before we even start building the robot.”

He has no worries that potential design faults identified in the simulation will lead to criticism of the human developers: “On the contrary, I believe that the simulation tools available today are a great help in the design process. They allow us to monitor entire movement processes, and the forces they generate, in advance and avoid costly mistakes. We’re also able to reduce the weight of the components without impacting on their stability.”

Should IRiS fulfil all expectations at the end of the project in mid-2020, then Dr Thamer expects there to be further development work before the robot is ready to go into production. The overall development costs of €3.16 million for the IRiS robot will not be included in the price of the end product, he says: “There’s plenty of room for optimisation based on the experiences gained from the test runs. When it comes to launching these systems on the market, they often come at a lower cost thanks to economies of scale.”

BLG is a pioneer in digitisation, thanks to its own Digilab, which brings the group into the future.

You can obtain further information on the logistics locations Bremen and Bremerhaven here or from Andreas Born, Innovation Manager Maritimes Cluster Norddeutschland and Industry 4.0 , +49 (0)421 361-32171, andreas.born@wah.bremen.de

Do you have any questions about the Bremen Technology Park or are you interested in commercial space or real estate? Then Anke Werner, Projekct Manager region East, +49 (0)421 9600-331, anke.werner@wfb-bremen.de, will be pleased to help you.

Success Stories

Profile of Bremen's eight ports

Bremen's ports are the engine that drives economic activity throughout the region. But do you know which goods arrive and depart, and where? We have taken a look around the eight port complexes in Bremen.

Learn moreThe Polymath from Horn-Lehe

No can do? No such thing! GERADTS GMBH makes the things other companies can’t even imagine. This is why this engineering firm is so firmly rooted in major European aviation and aerospace projects, and also in a myriad of other sectors.

Learn moreBremen's Economy in Figures: 2024 Statistics

A look at the statistics on Bremen's economy in 2024 reveals: Germany's smallest federal state has a lot to offer. An overview of the industrial and service sectors with the most important current figures.

Learn more